One of the biggest controversial topics in the world of nutrition is the role that carbohydrates play in weight loss/gain. There are numerous articles that talk about the benefits of low-carb diets for weight loss, but the reality is you can lose weight on a high-carb diet as well. Yes, it’s possible to lose weight on a low-carb diet, but the reasons why don’t come from decreased carb consumption. There are other factors in play which will be thoroughly addressed throughout this post. First, let’s identify an article that associates decreased carb consumption with weight loss:

How Many Carbs Should You Eat per Day to Lose Weight?

This article comes from the popular website Healthline.com. The article was published by a Registered Dietitian, so it’s easy to assume that the information published would be accurate. In fact, the only things mentioned which are true end up contradicting what the overall message of the article is trying to say, which is basically ‘limit carbs to lose weight’. Let’s further break it down while debunking some of the claims that are being made.

The article starts out by saying if you’re not looking to lose weight by cutting carbs, then you can follow the USDA’s guidelines which is consuming 45-65% of calories from carbs. If the USDA guidelines are recommending 45-65% of calories should come from carbs, it must mean there’s a valid reason behind that. In fact, carbohydrates are found in many foods which are universally known as healthy: fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. They provide fiber and are full of nutrients. By restricting carbohydrate intake, you’re restricting the amount of nutrients you could be getting in your diet. Let’s look at the nutrients of a popular, sometimes misunderstood, starchy vegetable: potatoes. Potatoes are a great source of potassium, fiber, Vitamin C, and Vitamin B6 (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 2025). While they do have a high glycemic load, meaning it can lead to sharp spikes in insulin levels due to the amylopectin content, some of the starch also consists of amylose, which is a resistant starch. Resistant starch has health benefits similar to fiber, and resists digestion in the small intestine. Heating and cooling a potato can increase these resistant starches found, which can reduce the glycemic load and lessen the blood sugar spike upon digestion of the potato.

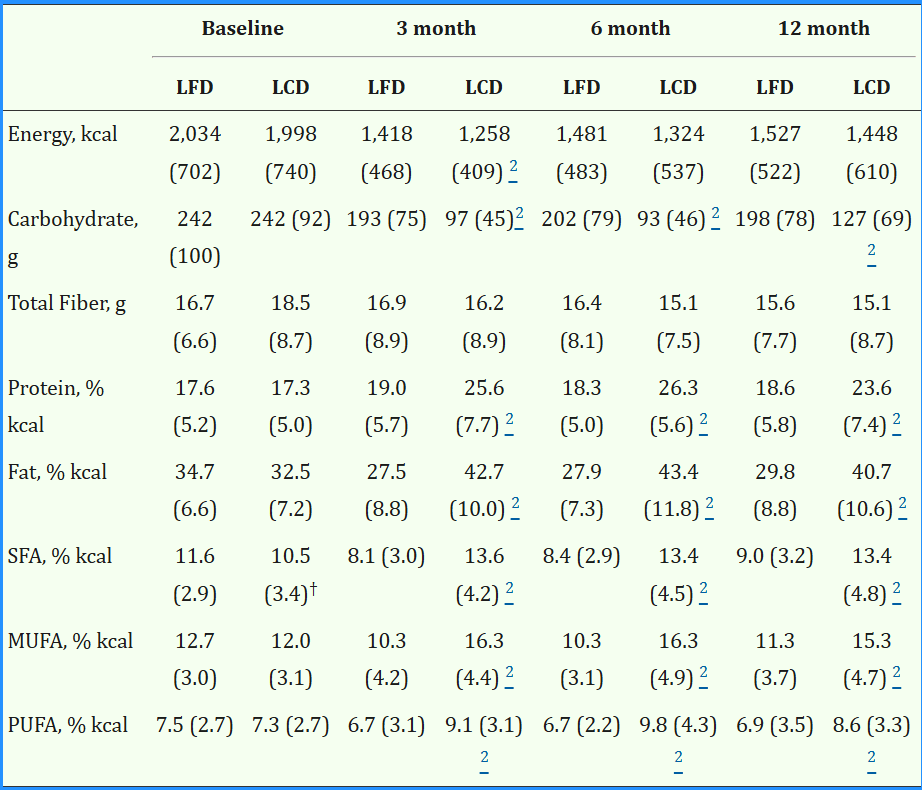

Continuing on, the article mentions that one of the benefits of eating less carbs is because it can reduce a person’s appetite. They reference a study comparing the effects of appetite suppression using two groups: one group which was adhering to a low-carb diet, and the other group which was adhering to a low-fat diet. They concluded that the low-carb diet group had bigger appetite suppression effects than the low-fat diet group, but upon inspection of the table that showed macronutrient intake in both groups, the low-carb diet group consumed higher percentages of protein (Hu et al., 2015, Table 2).

Table 2

Daily dietary composition in LFD and LCD groups

Note. Reprinted from “The effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite: A randomized controlled trial,” by Hu, T., Yao, L., Reynolds, K., Niu, T., Li, S., Whelton, P. K., He, J., & Bazzano, L. A. (2015), Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases, 26(6), 476–488 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4873405/). Licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Protein is the main macronutrient that leads to prolonged lowering of ghrelin levels, which helps to suppress appetite (Koliaki & Kokkinos, 2010). Protein is also known to increase peptide YY levels more importantly, which is the main hormone that the aforementioned study was researching and is associated with satiety (van der Klaauw et al., 2013). This means that it wasn’t the low carbohydrates impacting appetite suppression; it was the high protein intake.

Now let’s look at one of the contradictions found. When the article mentions a meta-analysis that compares low-fat diets to low-carb diets for weight loss over the period of 24 months, they concluded the meta-analysis found no difference in weight loss between the two groups after 24 months. Looking at the meta-analysis in-depth, it mentioned that after 6-11 months, the low-carb diet group lost 2.1kg more weight than the low-fat diet group (95% Cl, 3.07 to 1.14kg), and between 12-23 months, the low-carb diet group lost only 1.21kg more than the low-fat diet group (95% Cl, 1.79 to 0.63kg) (Lei et al., 2022). Even if we decide to omit the fact that out of the 33 RCTs involved in the meta-analysis, 6 were at high risk for bias, 3 were at low risk of bias, and the other studies had a moderate risk of bias, let’s understand why there could’ve been increased weight loss in the low-carb diet group after 6-11 months compared to the low-fat diet group. Carbohydrates are ultimately broken down into glucose in the blood. Glucose is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscle cells. For every gram of glycogen that gets stored, about 3g of water is stored with it (Fernandez-Elias et al., 2015). This means that depleting glycogen stores through a low-carb diet will unbind that water, and eventually get excreted. This will cause a rapid drop in weight loss initially. The meta-analysis was comparing weight loss in both groups, which includes water weight. This is perhaps why the low-carb diet group lost more weight in the beginning of the diets, because fat loss was not being studied specifically.

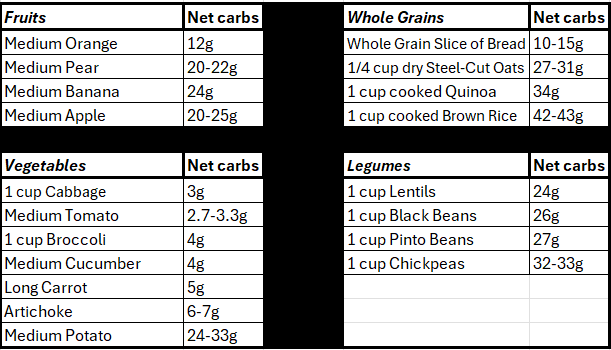

Another contradiction found is that the article mentions that high fiber carbs like vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains should still be eaten. This is because fiber isn’t a digestible carb, and it can be eaten in excess without having to worry about weight gain. But the foods that contain the fiber will still contain carbs in general, and the article doesn’t really give an exact answer for amount of carbs to limit daily. It just mentions that most low-carb diets will allow between 20 – 120g of carbs to be consumed daily, with the exact need varying between individuals based on multiple factors. So, the article isn’t giving a clear answer on recommended carb intake to lose weight, but is suggesting that 20 – 120g of carbs is the acceptable range. Let’s look at the net carb content of some of the foods that the Healthline article suggests should still be eaten.

Table 3

Net carbs listed in common fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes

Note: Data obtained from Google AI (2025)

Besides the non-starchy vegetables, the orange, and the whole-grain slice of bread, all of those popular examples contain at least 20g of net carbs. Does this mean if someone on a low-carb diet that’s sticking to a goal of 100g net carbs max daily consumes ¼ cup dry Steel-Cut Oats for breakfast, then a cup of quinoa for lunch, and a potato for dinner, they’re not allowed to have an apple, banana, or even a carrot as a late-night snack? The idea that you’d have to deny a nutrient-dense food just because you’re at your carb limit for the day and instead end up going for a ‘low-carb protein bar’ or something else that will probably contain more calories doesn’t make sense to me. We’ll get more into calories soon.

One of the reasons people associate carb consumption with weight gain is because of the hormone insulin. Insulin has several roles: glucose uptake into cells, facilitating glycolysis (the breakdown of glucose), glycogenesis (synthesizing glycogen from glucose), lipogenesis (synthesis of fatty acids from excess glucose), and also is known to inhibit lipolysis (the breakdown of fats). That’s why ‘insulin promotes fat storage’ is a phrase that’s tossed around all too often, and it’s mentioned in the Healthline article as well. Yes, it’s true that insulin promotes uptake of glucose into cells and stores whatever isn’t used as glycogen in the liver and muscle cells. After that, lipogenesis occurs, meaning whatever glucose remains circulating in the blood after glycogen stores are topped up will get stored as fat. But on a low-carb diet, when the body isn’t getting enough glucose from carbohydrates, the protein that’s consumed will undergo a process called gluconeogenesis, resulting in its conversion to glucose. This can lead to excess protein getting stored as fat as well, if calorie consumption is higher than what the body is burning off (Bray et al., 2012).

To set the record straight, calorie consumption is the biggest factor when it comes to wanting to lose weight. Proteins and carbohydrates contain 4 calories per gram, fat contains 9 calories per gram, and alcohol contains 7 calories per gram. It’s not about the amount of carbs you limit; it’s about the amount of calories you limit, regardless of the macronutrient they come from. There are two types of carbs: complex and simple. Complex carbs are generally healthy, unless they’ve been refined (the grain ends up losing the bran and germ while keeping the endosperm in the refining process). Simple carbs are sugar. Foods with natural sources of sugar are typically going to be healthier, such as fruit (contains fructose) or milk (contains lactose). Foods with added sugars are typically going to be calorie-dense and nutrient-poor (think baked goods, soda, candy, and ice cream). People on low-carb diets generally lose weight because they’re omitting tons of processed and refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, candy, and sweets. Simply put, those foods mentioned aren’t filling, meaning that eating them can lead to overeating, thus contributing to excess calorie consumption. Weight loss is as simple as energy in vs. energy out…and energy is in the form of calories. The first law of thermodynamics states that energy can’t be created nor destroyed, so assuming 1,000 grams of carbs will make you any more fat than 1,000 grams of protein is inaccurate, because they both contain 4,000 calories’ worth of energy.

In conclusion, carbs are not something that should be limited in the diet for the purposes of weight loss. They are not something that should be limited in general unless you have diabetes or another medical condition that is adversely impacted by carbohydrate consumption. If you really want to lose weight, reduce your calorie intake, and include in your diet plenty of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, lean proteins, and healthy fats. Even refined grains have a place in the diet since they’re often enriched with B vitamins and iron, and iron is the mineral that most people are deficient in (Kiani et al., 2022). Remember, there’s no such thing as a bad food…only a bad diet.

References:

Bray, G. A., Smith, S. R., de Jonge, L., Xie, H., Rood, J., Martin, C. K., Most, M., Brock, C., Mancuso, S., & Redman, L. M. (2012). Effect of dietary protein content on weight gain, energy expenditure, and body composition during overeating: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 307(1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1918

Fernández-Elías, V. E., Ortega, J. F., Nelson, R. K., & Mora-Rodríguez, R. (2015). Relationship between muscle water and glycogen recovery after prolonged exercise in the heat in humans. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 115(9), 1919–1926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3175-z

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2025, August). Are potatoes healthy? https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/potatoes/

Hu, T., Yao, L., Reynolds, K., Niu, T., Li, S., Whelton, P. K., He, J., & Bazzano, L. A. (2015). The effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on appetite: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases, 26(6), 476–488. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4873405/

Table 2. [Daily dietary composition in LFD and LCD groups over the course of the study].

Kiani, A. K., Dhuli, K., Donato, K., Aquilanti, B., Velluti, V., Matera, G., Iaconelli, A., Connelly, S. T., Bellinato, F., Gisondi, P., & Bertelli, M. (2022). Main nutritional deficiencies. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, 63(2 Suppl 3), E93–E101. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2752

Koliaki, C., & Kokkinos, A. (2010). The effect of ingested macronutrients on postprandial ghrelin response: A critical review of existing literature data. International Journal of Peptides, 2010, Article ID 710852. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/710852

Lei, L., Guo, H., Li, J., Zhou, Y., Xu, X., Liu, J., Zhang, L., Qi, M., Zhou, Y., Guo, T., Li, Y., Wang, H., & Zhang, X. (2022). Effects of low-carbohydrate diets versus low-fat diets on weight loss and metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese adults: A 6-month randomized controlled trial. PeerJ, 10, e13943. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13943

van der Klaauw, A. A., Keogh, J. M., Henning, E., Trowse, V. M., Dhillo, W. S., Ghatei, M. A., Tedford, C., Arno, M., Brain, S. D., Abdulrasheed, T., Papakostas, K., Schofield, C., Abbara, A., & Farooqi, I. S. (2013). High protein intake stimulates postprandial GLP-1 and PYY release. Obesity (Silver Spring), 21(8), 1602–1607. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20154

Leave a comment